When I began writing a nutrition column over twenty years ago, most dietitians or doctors did not have the topic, “where do plants come from”, on their radar . Both would agree that eating plenty of fruits and vegetables was a good health move, but there was no concern for the minutia. Nobody wondered how the Granny Smith apple came about, or how all of the broccoli heads were so uniform and dense (answer: plant breeding).

Fruits and vegetables were something you found in the produce, canned food, and freezer aisles. They were purchased based on quality, nutrition, and taste. Period.

Here we are, in 2019, and it’s “the future”. All sorts of things, beyond our wildest dreams, have been made possible by technology over the last fifteen years. This would include the wide variety of fruits and vegetables in the produce section of the modern supermarket.

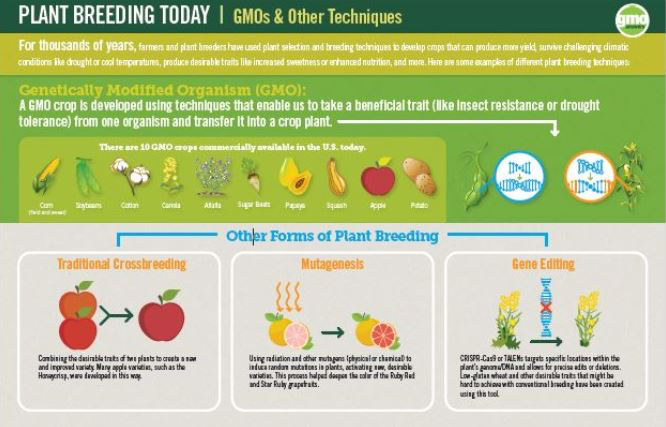

Plant breeders have been working on developing new strains and varieties of fruits and vegetables for a century or more. I’m sure there are fruits and vegetables you buy now that you never saw when you were younger. It’s just that now, the term “GMO”, or genetically modified organism”, has everyone concerned and confused (and “non-GMO” labeling adds to this confusion).

What is a GMO?

When it comes to the plants we eat, GMO is just referring to a method of plant breeding. Lots of plant breeding techniques used over the past century to create better yield, quality, or quality, have produced crop which are technically “genetically modified” by traditional methods, but they aren’t defined as “GMOs”.

It’s likely that a lot of things you may think “are GMO”, aren’t. A GMO crop is developed by taking a specific desirable gene from one organism and transferring it to another.

That seedless watermelon you love? Plant breeding (but not GMO).

The yellow varieties of tomatoes? Plant breeding (also not GMO).

There are Currently 10 GMO Crops in US Market

To understand a little about what GMO means, you have to have a basic understanding about plant breeding. The infographic below from GMO Answers shows three types of plant breeding: Traditional cross-breeding, mutagenesis, and gene editing.

Traditional cross-breeding works by breeding two closely related plants (of the same species) together. Apples are a great example, as most everyone is familiar with the numerous apple varieties available in the US market.

Mutagenesis involves using radiation, or another application, to modify the genes of a plant (and sometimes mutations just happen on their own). Mutagenic breeding has provided us with lots of improved crops (including rice, wheat, barley, pears, peas, peanuts, grapefruit, bananas).

Transgenic breeding and gene editing are two types of GMO breeding techniques. Unlike the random results of traditional cross breeding, the DNA of the crop resulting from gene editing is precisely predicted.

How it Works

Have you ever seen anti-GMO articles with images describing genes from a completely different species being put into a plant (images that show hypodermic needles going into a vegetable or fruit)? This is NOT HOW IT WORKS. Our food does not get “injected” with anything. The breeding happens in the plant lab and greenhouse, on a cellular level.

Every GMO plant may not have been created using the same type of genetic modification process. Transgenic breeding involves taking genes from one species and inserting them into another. Corn, soy and canola are examples of this type of breeding.

Gene editing is a genetic engineering technology involving the manipulation of genes within one species. This technique is a very accurate way to target desired traits in a plant species. Sections of DNA are precisely “snipped” based on desired traits (CRISPR, or ‘clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats’, is a type of DNA sequence, targeted in some gene editing technology). The Arctic® Apple is one of ten GMO crops currently on the US market, and is an example of a crop developed through gene editing. In the case of this non-browning apple, the oxidative browning enzyme was silenced, so that the apples don’t brown when cut and exposed to air.

Give GMOs A Chance

The idea of “genetic engineering” may seem “unnatural”. It’s hard to picture what a “gene” looks like. Genetic modification can bring lots of options to the plant breeding process. Rather than spending years on trial and error, using gene editing in plant breeding can save time and money. For the most part, genes from the same species are inserted into a similar species. In other cases, genes within the species are modified by either rearranging, silencing, or removing.

Rather than taking a stance to be “Anti-GMO” when it comes to food, consider that it’s a form of plant breeding. There are multiple methods of gene modification, and that there is huge potential in this area to solve modern problems when it comes to growing food (pest problems, browning, disease, or problems associated with drought conditions). In addition, future GMO crops may also be developed with specific nutrition goals in mind (higher antioxidant content, better flavor profiles, more vitamin, minerals or other nutrients).

Another thought – trust scientists who are experts in a particular area. I am not a plant geneticist nor an expert in plant genetics. Most university professors and researchers are happy to address questions about their areas of expertise.

The more you can learn about the plant breeding methods plant scientists use, the better you’ll feel about GMOs.

More information: The Genetic Literacy Project and GMO Answers.

Yep, Everything needs at least some level of knowledge to be able to properly judge it. But people just love to fear what they don’t know.