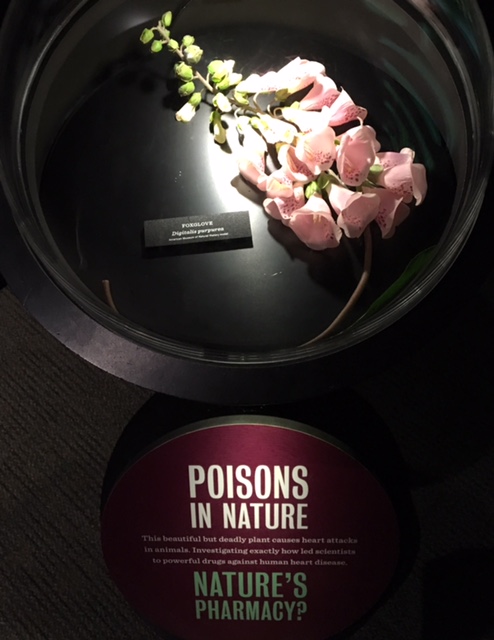

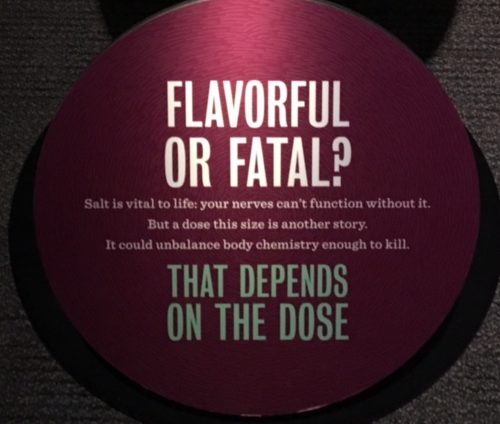

Photo taken at Power of Poison in the Natural World exhibit, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

What’s worse, sugar or fat? Is salt good or bad? How much of it should you include in your diet? Will a “sugar detox” improve my health? Are plants sprayed with glyphosate poisoning us?

These are questions I hear often. There’s much debate about which substance in our diet is the most harmful, and the big picture is often lost when we focus on one substance, such as sugar, fat, or salt. In actuality, there are upper limits set for just about every nutrient.

When debating whether salt, fat or sugar, glyphosate (a weed control herbicide) and more recently, vegetable oils, may impact your health, it’s really important to understand the concepts of hazard and risk.

Hazard Versus Risk

Since taking a toxicology class in grad school, I’ve always been fascinated with the human body’s response to toxins and the presence of natural toxins all around us. As a dietitian, you may not think I’d need to understand anything about toxicology, but there are many basic principles of toxicology that are actually very important to understand.

I recently took a trip the the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh where they are hosting an exhibit this summer called The Power of Poison in the Natural World. The exhibit illustrated this difference using a broad range of poisonous hazards within nature around the globe.

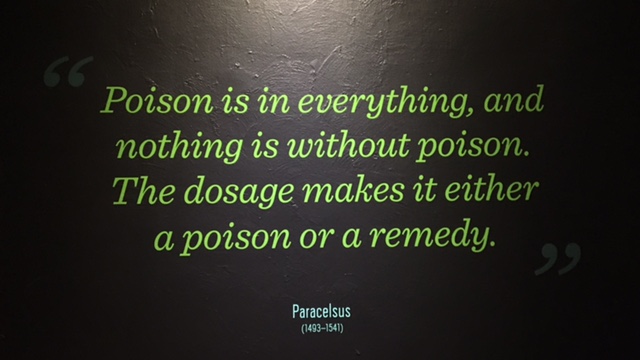

The adage “the dose makes the poison” is one I use often, both in my professional discussions as well as during dinner table chats. This notion of dosage describes the simple difference between a substance being a “risk” versus a “hazard”. Hazard is defined as something that can cause harm. Epidemiological nutrition studies consider how a hazard may pose harm by increasing risk of diseases like cancer, or damage to major organs (liver, kidneys, lungs, or the reproductive system), or something that can cause birth defects or have neurotoxic effects.

A hazard is defined as something that can cause harm. Risk is the potential for a hazard to cause harm. Click To Tweet

The Dose Makes the Poison

An example would be the foxglove, or digitalis, plant. We have this beautiful flower growing in our wildflower garden. It’s beautiful, but toxic in the wrong dose. The plant is used to make the drug digoxin, which has been used for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. So sometimes small amounts of toxins (or hazards) can actually produce beneficial properties. The dose makes the poison.

Snake Bites Versus Our Diet

As my science-loving son often reminds me, most snakes won’t hurt you unless taunted. A viper presents a hazard when the snack bites, but risk increases if you get in its way and pursue it. You reduce your risk by leaving snakes alone when you see them. (Fun fact: baby snakes are more hazardous than adult snakes, because they lack control of the amount they venom they inject into their prey).

Risk equals hazard plus degrees of exposure. In the case of a bite from a venomous pit viper, the outcome is grim, as any level of exposure to that sort of venom is debilitating or even deadly, depending on the speed of anti-venom treatment.

How much is too much

The degree of exposure to components of our diet however are a bit different. I could put a half teaspoon of sugar on my oatmeal, eat two Hershey Kisses, have a glass of wine, eat 2 pieces of fruit, drink 6 ounces of orange juice, and enjoy a half cup of ice cream, every single day and not be at risk for sugar poisoning. I can also cook with salt, consume processed meat for lunch twice a week, and used canned food daily, for example, and not be at risk for salt poisoning. Overheating oils over and over again (as in a food fryer) may pose risks, but mixing up a salad dressing or pan frying food in a tablespoon of oil, is not an issue.

Are Americans poisoning themselves with sugar or salt? I don’t think so. It’s not necessary to “detox” by completely eliminating the hazard. Think about all of the hazards you encounter every day: the sun, the road, insects, the bleach you may use to brighten your clothing or disinfect something, your pet, your plants, soap, wine. Would you want to completely eliminate all them by never going outside, not planting a flower pot, not bathing, and not leaving your home? Never visit another winery?

In reference to a large bowl of salt which could be fatal. Photo taken at Power of Poison in the Natural World exhibit, Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Be Sensible

You can drink too much wine. You can expose yourself to too much sun without sunscreen. Could some people reduce how much sugar or sodium they consume? Absolutely. The question is – do scare-tactics motivate you? There are always some ex exceptions however here are some simple ways to reduce your sugar and salt intake:

- Drink more water to quench your thirst in place of soft drinks or lemonade. Substitute sparking waters or diet soda for regular. If you love soda, set a goal to limit it to 12 ounces or less daily (if you have diabetes, or need to lose weight, you should completely eliminate it).

- Limit desserts and bakery items such as cinnamon buns, donuts, danish, cake, cookies, to no more than twice a week or so.

- Limit your portion of ice cream. Summertime screams ice cream right? Enjoy it in smaller portions. Order the small cone or sundae. Fill a small ramekin to portion out ice cream at home.

- Eat less candy and avoid “King Size” (unless you share it).

- Shake less salt on your food, and read labels for sodium. Choose more low sodium foods.

- Enjoy bread and cereal, but reduce the number of servings you consume in a day (3-5 servings, with one slice or 6-8 crackers, or about 1 cup of cereal being one serving).

- Read labels on seasonings and choose more salt-free herb blends, and spices, in lieu of salts.

- Don’t reuse oil, once you cook with it.

- Calm down. Eat and drink sensibly.