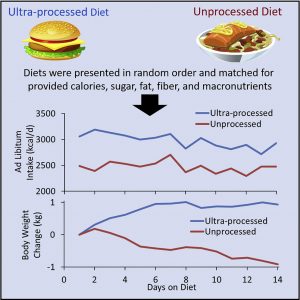

You may have read several news pieces about the recent study comparing two small groups of people who were offered the same amount of calories of either “ultra-processed food” or “whole foods”, but only the ultra-processed food group gained weight. The authors then conclude:

“Limiting consumption of ultra-processed foods may be an effective strategy for obesity prevention and treatment.”

How can this be you ask? Well, the subjects were presented with three daily meals and were instructed to consume as much or as little as desired. Twenty people (with BMI around 25-29, stable weight, yet slightly overweight) were placed into two groups – one that offered ultra-processed food, the other offered whole foods. Both groups were offered the same amount of calories, but different food. The group offered the ultra-processed food ate more of their ration (about 500 calories more daily), and therefore gained weight over the 2-week observation period.

It’s frustrating to me when anyone wants to water down the complexity of obesity. It’s not that simple. Lifestyle, medical history, genetics, stress levels, age, activity – all impact body weight.

I don’t think this study was a revelation to any registered dietitian who’s spent years interviewing clients, taking diet histories, and counseling people. The 1970’s marketing campaign of “you can’t eat just one” potato chip, still rings true when it comes to salty or sweet snack foods.

For example, let’s compare eating potato chips (“ultra-processed potatoes”) and baked potatoes (whole food). Most people could easily eat 300 calories (2 ounces) of potato chips in one sitting (and still be “hungry”). They may have a harder time eating the same amount of calories of whole potatoes (2 medium-sized baked potatoes) in one sitting. You could also wolf down the 300 calories in chips much more quickly than the 2 whole potatoes.

A Comparison of Extremes

Popular diet advice seems to be stuck in a mentality of extremes. You’re not told to just “reduce carbs” you have to go “ultra low carb”. You can’t just add a little bit more healthy fat or protein into the diet, it has to be high fat and high protein. I have never subscribed to this all or none philosophy. It doesn’t work for most people long-term, and it’s often completely unnecessary.

This study used the definition of ultra-processed food as “formulations mostly of cheap industrial sources of dietary energy and nutrients plus additives, using a series of processes.” It compared two very different extremes – a diet that is filled with ultra-processed to an ultra-idyllic diet of fresh, whole foods. Neither of those scenarios is realistic or necessary to achieve a healthy dietary pattern. Furthermore, the study’s implication that if you avoid ultra-processed food and start eating whole foods, and cooking more, you won’t gain weight and you’ll be healthier – is a stretch.

At the surface, this statement is partly true – Over consuming ultra-processed food isn’t healthy choice, but the notion that simply eliminating them from your diet is a solution to weight control, completely minimizes the time, skill, and effort it takes to shop for ingredients and cook food on a regular basis. It also doesn’t address how overall dietary patterns impact health.

Dietary Patterns

And that’s the thing – there is a different between what you eat at one meal, in one day or in one week or month. Your dietary pattern includes the foods you consume over weeks and months. Not single meal conveniences.

My concern is the details of the definition of processed food will get lost in the headlines from this recent study. The study suggests there’s one ideal, but there are actually many ways to create basic, balanced meals, and some processed foods can be used to do it.

Many processed foods (canned beans, vegetables, rice, pasta, frozen meal kits) provide great nutrition for healthy inexpensive meals you can prepare easily at home. For example, it’s also a myth that canned or frozen foods is associated with poor diet quality. Canned and frozen fruits and vegetables are processed, but not “ultra-processed”. There’s research showing that diet quality can actually be enhanced by including canned fruits and vegetables.

Idealistic meals also don’t address other socioeconomic issue such as “food deserts”. People who don’t have access to the grocery store, or other markets with fresh food, are at a disadvantage. They may not have transportation or a corner store is their only choice. They may prioritize paying rent or the gas bill over food. They may have not only very limited food choices, but may not have a kitchen, stove, or cooking utensils available to them. They may also be in a socio-economic situation where a dollar “meal” consisting of a candy bar and a sugary drink is what they can afford in that moment to survive.

In other less extreme (and perhaps more widespread) instances however, it’s not the food desert or lack of choice, but a lack of skill or failure to prioritize the value of nutrition and its role in health and well-being. Dietitians who work in community nutrition settings are always working toward helping people make the most of their food budgets and resources; working together to help people understand nutrition basics and get exposed to new foods and flavors.

But even then, it’s going to take more than just “eat less ultra-processed food” messages to improve health and diet quality of a growing population. Taste preferences, food exposure, cultural influences – all impact what people eat. If one is brought up on ultra-processed food, they are not going to accept a piece of grilled salmon salad overnight (as the figure below from the recent study suggests). We need real solution to “better” choices that are reasonable, not “ideal” ones.

Downloaded from: https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(19)30248-7

Back to Basics with Budget-friendly Meals

To get better meals to more people we need to start talking about meal planning in simple terms. Not fancy food, but simple basic meal planning. You don’t have to shop at a Whole Foods® market, use fancy ingredients, “buy local”, or have farmer’s market access to eat a less-processed diet.

There are many resources available about healthy nutrition and planning healthy budget-friendly meals. The challenge is, getting this information to folks who need it, and helping them learn both cooking and nutrition basics. This process can start in schools with the school lunch program (which exposes children to new foods they may not otherwise be exposed to at home), home economics curriculums, or in the community at local farmer’s markets and grocery stores where recipes and cooking demos may be available.

Simple, healthy diets can be planned from basic unprocessed foods (meats, dairy, grains, vegetables and fruits). Agricultural organizations such as the Beef Checkoff and Pork Checkoffs have always provided free nutrition information, recipes, cooking tips, and doable meal planning ideas for all budgets. The National Dairy Council also provides budget-friendly ideas for adding nutrition to the diet. On the plant front, the Grains Foods Foundation provides simple recipes for grain-based meals, the Produce for Better Health Foundation provides ways to add more plants to your diet and choose the least expensive produce, and the Canned Food Alliance offers facts about how canned foods can add inexpensive protein, fiber and vitamins and minerals to your diet.

Nutrition and health care professionals (and journalists) need to come together and agree that better, or decent, nutrition is an admirable goal. The longer we hold up this “salmon salad on fresh field greens” or the “flax seed green smoothie” or “the plant forward diet”, as “ideal” nutrition for everyone, the further away we’ll be from improving diet quality for those who really need it.

Bravo! You are so on target, Rosanne. There is definitely a happy medium between every meal being fresh foods cooked from scratch and every meal being fast food or boxed convenience food. Thanks for being the voice of reason!

Thank you! Absolutely. While ultra processed food are certainly easy to over-consume (often due to high oak stability and low fiber), using some processed foods is essential for most people. Items like canned beans or fruit, quick cooking rice, ready-to-eat cereals, make getting healthy meals into the table easier.